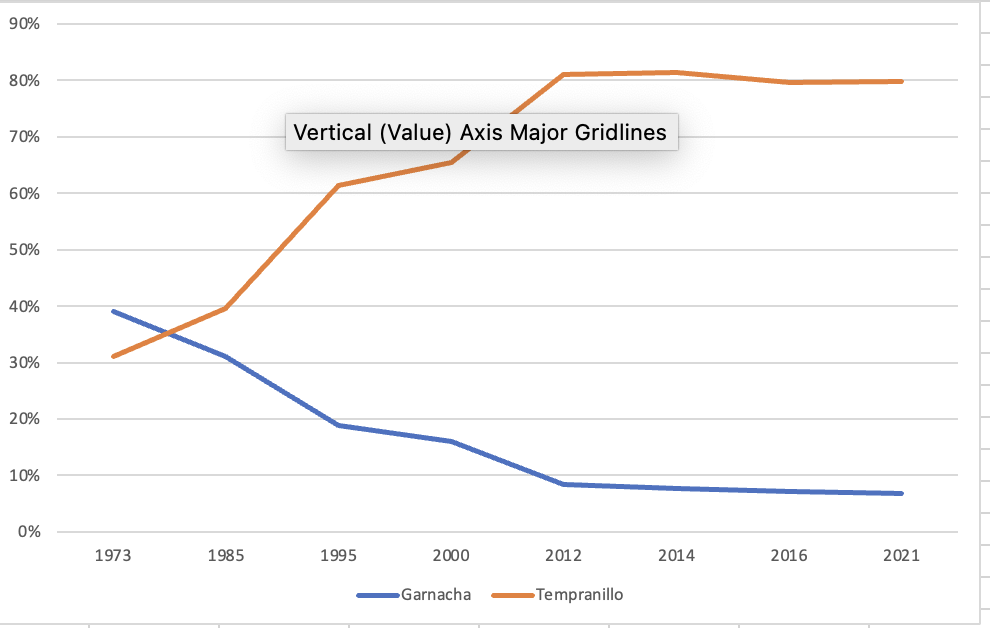

What is the most iconic factor that defines Rioja? It would certainly be tempting to say that it’s the tempranillo grape. After all, it’s the most widely planted varietal here, with 88% of red varietals and 80% of the total area under vine. But it wasn’t always so. According to the 1976 vineyard census, the area planted to garnacha was almost twice that of tempranillo (12800 hectares vs. 7000) and it wasn’t until the early 1980s that the latter overtook the former.

Tempranillo is Rioja’s dominant grape variety but the Rioja blend is king

‘Rioja’ has been associated with a wine region for several hundred years, so the increasing dominance of tempranillo in the last forty years can scarcely be the basis for elevating this grape to the status of an icon. In fact, Alberto Gil, the wine columnist for our regional newspaper La Rioja, refers to the “tyranny” of tempranillo for its ubiquity. ‘Dominant’ is not a synonym for ‘iconic’.

For historical reasons based on the region’s location at the confluence of Atlantic and Mediterranean-influenced climate types, a more appropriate icon in Rioja might be the classic Rioja blend of tempranillo, graciano and mazuelo for reds meant for ageing, and tempranillo and garnacha for young reds. Ángel Jaime y Baró, longtime director of the Haro Viticultural Laboratory and later, president of the Rioja Regulatory Council, called it “typicity”-what made Rioja recognizable and well-liked by consumers in Spain, and, with the Rioja “boom” beginning in the early 1970s, in the UK and from there, around the world.

Garnacha vs Tempranillo %

To understand the importance of the Rioja blend, we have to go back more than one hundred years to the fight against phylloxera when it first appeared in a vineyard near Haro in 1899.

Agronomist engineers defined and refined the Rioja blend

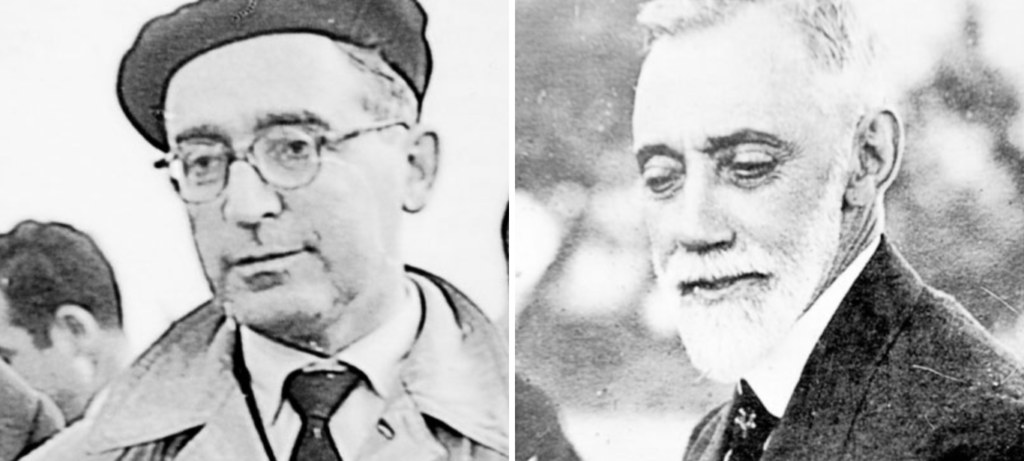

Leading the fight were two agronomist engineers, Nicolás García de los Salmones, director of the Agricultural Research Laboratory in Navarra and Víctor Cruz Manso de Zúñiga, the second director of the Rioja Viticultural Research Laboratory in Haro.

Antonio Larrea and Víctor Cruz Manso de Zuñiga. Photo: Estación Enológica de Haro.

In the late 1800s, García de los Salmones traveled throughout French wine regions documenting the practice of grafting European varietals onto American rootstock while at the turn of the 20th century, Manso de Zúñiga concentrated on a scientific approach to rebuilding Rioja’s vineyards on the basis of detailed analyses of the region’s soils and climate patterns.

The regional governments in neighboring Navarra and Álava were responsible, thanks to García de los Salmones and these governments’ fiscal independence from Madrid, for purchasing a large supply of

American, phylloxera-resistant rootstock as well as financing plant nurseries. No such large-scale assistance was available in La Rioja until the creation of the Caja Vitícola Provincial, a bank that issued debentures and then lent money with generous terms to farmers with which they could purchase rootstock, plants, machinery and other products necessary to rebuild their vineyards.

One of the requirements for these loans was that only certain varieties could be planted including ‘more tempranillo and less garnacha’. This led to Manso de Zúñiga’s definition of the ideal Rioja blend as ’75% tempranillo, 15% garnacha and 10% mazuelo’.

Antonio Larrea was the director of the Haro laboratory for 30 years (1944- 1970), followed by assuming the presidency of the Rioja Regulatory Council. Larrea further refined the definition of the Rioja blend in 1956 when he recommended “75% tempranillo, 15% graciano and 10% mazuelo”.

Manso de Zúñiga and Larrea saw where these varieties fit in the puzzle made up of the long, narrow upper Ebro valley with its seven tributaries, hills, valleys, and soils ranging from mostly limestone, iron and clay in the cooler, wetter western half and alluvial in the hotter, drier eastern half.

Teaching viticulture and winemaking to a generation of Rioja winemakers

Larrea was responsible for the practical viticultural and enological education of a generation of young university graduates, many of whom, like Ezequiel García and Gonzalo Ortiz, would go on to work in Rioja’s leading wineries. Others would study winemaking in Bordeaux where they learned about blending cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc and merlot.

Manso and Larrea understood the characteristics of Rioja’s four red varietals, where they were best expressed in the region and how they complemented one another.

Armed with this knowledge, winemakers could compensate for the negative effects of weather on vineyards in a particular growing season by buying grapes and wine from all over the region as well as blending wines from different vintages to create a consistent style from year to year.

Rioja in those days was ‘made’ in the winery.

Neither Manso nor Larrea could imagine, however, the expansion of vineyards planted to an easily cultivated variety like tempranillo to the detriment of the other varieties because of the explosion in demand for Rioja beginning in the 1980s.

A single varietal Rioja was hard to accept

Rioja was so associated with the concept of the blend that the first single varietal tempranillo, Viña Alcorta, created by Bodegas Campo Viejo, the largest winery in the region, was at first criticized by wine writers in Spain who thought that “something was missing”.

Since Alcorta’s launch in the mid-1980s, a torrent of water has flowed under the Rioja bridge, with an increasing focus on terroir (the natural environment of a vineyard that includes climate, soil, and topography), the creation of single varietals, single vineyard wines, single subzone wines, single village wines, the use of a wide range of oak for barrels and the introduction of old Riojan varieties rescued from extinction. The land of typicity has become “the land of a thousand wines” but the sheer dominance of tempranillo makes it the overwhelming grape in a Rioja winery’s varietal palette.

Nowadays the conversation in Rioja is all about terroir and specificity, with a focus on the vineyard, which almost always means a single varietal. The Rioja blend however, has a long history and certainly deserves to be called iconic.

Text by Tom Perry, Inside Rioja